“Rising Above” Excerpt: Stephen Curry

There wasn’t a single college willing to give Stephen Curry a chance. His dream of playing professional basketball seemed a long shot. A really long shot.

It was 2004, and Stephen was a high school sophomore. His father had played pro basketball and been a star. Steph grew up in North Carolina, close to some of the best college programs in the country, an ideal place to showcase his talent for top NCAA programs. And Steph had a passion for basketball, an accurate shot, and a hunger to make it to the NBA.

But no one took Stephen very seriously. He kept hearing how he was too tiny and skinny to play Division I basketball, the top collegiate level. The NBA seemed truly out of the question. It didn’t help that Steph had a boyish look, making him appear even younger than his seventeen years. Big-name schools kept passing on Steph, figuring he couldn’t contribute much to their basketball programs.

Those were the schools that actually knew Steph existed. Most of the best coaches hadn’t even heard of him; they sure weren’t going to recruit him or offer him a scholarship.

“I don’t even remember seeing him [during his college recruitment process],” says Roy Williams, the legendary University of North Carolina coach. “I do know when I did see him I thought, ‘Man, he is little.’”

Earlier in life, Steph seemed to have a lot going for him. Steph’s father, Dell Curry, had been a first-round draft pick who’d played sixteen years in the NBA for five different teams. A six-foot-four shooting guard, Dell had retired from the NBA after a long career and remains the Charlotte Bobcats’ all-time leading scorer and three-point shooter. Steph’s mother, Sonya, had been both a basketball and volleyball state champion in high school and played varsity volleyball in college.

With such a rich athletic tradition in his family, Stephen played and enjoyed a lot of different sports growing up. But basketball was his first love.

“I was a competitive guy,” Steph said in an interview on ESPN, “but something about basketball and doing what your dad did [made basketball] more of a draw.”

Having a father in the NBA was a thrill, and Steph grew up admiring his dad and his skills on the court. His mother wouldn’t let him go to Charlotte’s games on school nights, though, worried he’d be exhausted the next day and unable to concentrate on his studies. So on weekends, Steph and his younger brother, Seth, attended as many of their father’s games as they could. It was exciting seeing the best NBA players up close; it was even more fun watching their father compete against them. Steph and Seth sometimes even got to shoot with Charlotte players during pregame warm-ups.

In eighth grade, Steph decided to dedicate himself to basketball, determined to follow in his father’s footsteps. He began practicing year-round, committing himself to doing “whatever it took, whatever was necessary, to play in college,” he says.

By the time Steph was a sophomore in high school, however, he ran into an imposing roadblock: He was just too small. Steph stood five foot six and weighed in at a scrawny 125 pounds.

“On every team he ever played on, he was the smallest guy,” his father says.

Steph was so frail that he had to begin his shooting motion well below his waist because he lacked the strength to raise the ball and shoot it from above his head. Steph’s father knew there was no way his son could play college ball if he didn’t change his approach. Shooting from below the waist makes it far too easy for a defender to swat the ball away. Dell knew college coaches never would recruit a player with that kind of shooting form.

One day, Dell came to Steph to deliver some unsolicited advice.

“If you want to play in college,” Dell said, “you’re going to have to bring [the ball] up and get it above your head.”

Steph was happy with his shot and wasn’t sure he needed to make such a dramatic adjustment. But he eventually understood he'd need to transform his game if he wanted to play with bigger and better players, as his father had advised.

Given his size, the NBA seemed completely out of the question for Steph, but he still wanted to play college ball, so he agreed to let his father tutor him. Steph took the summer off from his usual activities, even from playing pickup basketball games, to focus on reinventing his jump shot.

He didn’t realize how difficult the process would be. All summer long, he and his father practiced and practiced on a hoop in their backyard. But Steph didn’t seem to make much progress. Some nights ended in tears.

“It was tough for me to watch them in the backyard, late nights and a lot of hours during the day, working on the shot,” Seth, Steph’s younger brother, told ESPN. “They broke it down to the point where he couldn’t even shoot at all. . . . He had to do rep after rep after rep to the point where he was able to master it.”

“That was a tough summer for him,” Dell agrees.

Steph worked with his father on changing his release point and moving the ball above his head in order to make his shot harder for rivals to block. Steph wasn’t very muscular, so it was hard making the transition. But eventually the lessons kicked in and he began to master the above-the-head shot.

As they practiced, Dell and Steph developed a unique approach that made his shot both quick and accurate. When most players learn to shoot, they’re taught to release the ball as they reach the highest point of their jump. But Steph was learning to shoot on the way up, when he wasn’t very far off the ground. By shooting as he was jumping, rather than at the top of his jump like most people did, Steph could release the ball lightning fast, in as little as 0.3 seconds. That quick-shot technique would give him an advantage over defenders the rest of his life.

Shooting on the way up rather than at the top of his jump also enabled Steph’s shot to take the form of a sharp arc, like a rainbow, making it much easier to swish through the net. Unlike everyone else, Steph’s shots came in on a high angle, as if they were on a steep, downward slope to the opening of the basket. It was a distinctive approach he has maintained, more or less, throughout his playing career, according to the Wall Street Journal.

Back at school for his junior year, Steph’s hard work began to pay off. That year, he averaged nearly twenty points a game. He also had a late growth spurt. By the time he graduated high school, Steph was six feet tall and weighed 160 pounds. He’d grown half a foot and gained thirty-five pounds in two years. Steph led his team to three conference titles and three play-off appearances and was named an all-state and all-conference player his senior year.

Steph seemed to be on the road to greatness and began envisioning himself playing for a nearby college power. “Growing up in Tar Heel country, you want to play for Duke, NC State, Carolina, Wake Forest,” he says.

Yet none of those famed schools had any interest in Steph. Recruiters thought he was still too small and thin to excel at the collegiate level. Steph was developing a sweet stroke from the outside, but he just didn’t seem like someone who could create his own shots, deal with bigger defenders in his face, and play in college, at least at the Division I level. Some overlooked high school players excel in Amateur Athletic Union leagues, gaining the attention of colleges through that route, but Steph wasn’t an AAU star, either.

While most of the biggest schools had little interest in Steph, it made sense that his father’s alma mater, Virginia Tech, might be willing to offer him a spot on their team. Dell had been one of the school’s greatest basketball players, after all. And Virginia Tech doesn’t usually go deep in NCAA tournaments, so the school often recruits high school players like Steph—capable and hardworking but with little chance of becoming NBA stars.

But even Virginia Tech, which plays in the competitive Atlantic Coast Conference, decided Steph didn’t deserve a scholarship. The only way he could play on their team, the school’s recruiters said, was if he “walked on,” or tried out and outplayed someone else to earn a place on the team. They weren’t going to guarantee a spot for Steph and wouldn’t offer him a scholarship, no matter what his father had done at the school.

“I don’t think he ever said it,” Seth says. “But you could tell it hurt him.”

Steph tried not to get discouraged, hoping a small school might give him a chance. That summer, Steph focused on refining his game and improving his shot, using the brush-offs as motivation.

The right college and coach will come, he told himself.

Steph needed someone to believe in him. He found that person in Bob McKillop, the coach of Davidson College, a tiny liberal arts school located twenty minutes north of Curry’s home. Coach McKillop knew all the famous universities had passed on Steph, but he had a feeling they were making a big mistake.

Like other coaches and recruiters, Coach McKillop saw the deficiencies in Steph’s game.

“He looked thin, frail, and not strong,” Coach McKillop says.

The coach knew something others didn’t, though. His son had played Little League baseball with Steph as a ten-year-old, and Coach McKillop got to know Steph, watching him on the field, game after game. He continued to follow Steph closely in high school and knew Steph had special talent.

That’s not what convinced him that Steph could be a star at Davidson, though.

“You could see the character, the poise, the work ethic, toughness, and resiliency,” he says.

Coach McKillop got in touch with Steph and tried to convince him to enroll at Davidson, offering him a full scholarship. Sure, Davidson was tiny, with fewer than two thousand students and an average class of just fifteen. The college was best known for its academics and hadn’t won an NCAA tournament game since 1969, let alone any major tournament. But at Davidson, Coach McKillop insisted, Steph could be a difference maker, a player with immediate impact. Trust me and the program, the coach told Steph. Good things will happen, he assured Steph.

Steph believed in himself and was confident he could enroll in a more famous school and make the basketball team as a walk-on. But even if he managed to make a big-time college team, Steph knew he likely wouldn’t get much playing time. Maybe a few minutes here or there in mop-up duty at the end of a blowout. Playing a minor role on a team wasn’t what Steph was hoping for, however.

Coach McKillop was the first college coach to make Steph feel he was wanted and that he could excel in big-time basketball. With that in mind, Steph signed on to go to school at Davidson.

“I could have walked on at an ACC school,” Steph says. “But I wanted the opportunity to play.”

In his very first collegiate game, Steph got the start at shooting guard, a sign of the confidence Coach McKillop had in him.

It was a huge mistake.

The game was against favored Eastern Michigan on their campus, twenty minutes outside of Ann Arbor. Curry and his Davidson teammates fell behind early and trailed by sixteen points at halftime, an early destruction. By halftime, Steph had nine turnovers. He would finish with a humiliating thirteen turnovers in total.

Steph seemed truly out of his league in Division I basketball, just like the college coaches had predicted. In one embarrassing play, Steph handled the ball in the backcourt, as defenders swarmed around him, and quickly lost his footing. Slipping and falling to the court awkwardly, Steph flung the ball to a teammate, only to see an opposing player step in and knock it away. The Eastern Michigan fans cheered wildly, celebrating the ugly mistake. Davidson fans cringed.

At halftime, even Steph’s coach had second thoughts about him. “I’m rethinking whether he belongs in the starting lineup,” Coach McKillop remembers contemplating.

In spite of his reservations, Coach McKillop decided to leave Steph in for the second half, hoping he might settle down. Smart move. Almost immediately, Steph and his team began to rally. Instead of acting discouraged or scared after the awful first half, Steph called for the ball, camping out on the three-point line, begging teammates to feed him the rock. Steph began knocking down threes, one after another, becoming more confident with each bucket. He quieted the hostile crowd and led Davidson to an improbable comeback victory.

It was an early sign of Steph’s self-assurance and tenacity.

The next night, against an even more imposing University of Michigan team, Steph really went off. He scored thirty-two points, dished out four assists, and even snatched nine rebounds.

Steph finished his freshman year as the leading scorer in the Southern Conference, averaging 21.5 points per game, second in the nation among freshmen, just behind University of Texas forward Kevin Durant, a future NBA superstar. Steph also broke the freshman season record for three-point field goals.

One day that year, Coach McKillop spotted Steph’s parents in the airport and walked over, making a prediction: “Your son will earn a lot of money playing this game one day.”

Dell Curry was skeptical. A great college shooter is one thing. Making it at the pro level is a whole different ball game. Even though he’d had a late growth spurt, Steph was still short and slight, especially compared with guys in the NBA. Guarding big, muscular players in the pros seemed improbable. As far as Dell was concerned, Steph’s chances of succeeding in the NBA, or even getting drafted by a team, weren’t very strong; Coach McKillop’s prediction seemed foolish.

“I’m thinking, ‘Yeah, maybe [he’ll have a chance to play] overseas,’” Dell Curry says.

But Steph kept growing, reaching six foot three inches by his sophomore year in college. And he continued to perfect his shot. On March 21, 2008, Steph and Davidson played in the NCAA Tournament. With his parents in the stands and a national audience glued to their television screens, Steph dropped an astounding forty points on Gonzaga University, shooting an astonishing eight for ten from three-point range, leading Davidson to its first NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament win since 1969. Two days later, Steph burned heavily favored Georgetown University, the nation’s eighth-ranked team, for thirty points in another upset victory.

His parents watched from the stands, absolutely stunned. Steph was evolving from a good player into a great one before their eyes.

“Can you believe that?” Dell asked his wife.

They were so shocked they drove home from the game in silence, Steph’s mother, Sonya, recalls.

During that year’s tournament, Steph emerged as a household name around the country, becoming only the fourth player in history to average at least thirty points in his first four NCAA Tournament games and leading Davidson to the Elite Eight, where the team lost to the top-seeded and eventual champion Kansas Jayhawks.

“He changed from him being Dell’s son to Dell being Steph’s father,” Seth says.

Steph’s head-turning performance on a national stage dramatically altered the way he was viewed in the basketball world and beyond. After the NCAA Tournament ended, his parents saw up close how much Steph’s life and career had transformed in just a few days. At a Charlotte home game, they watched fans mob Steph, as if he was a rock star.

“That’s how I knew things had changed,” Sonya says.

After leading the nation with an average of almost twenty-nine points per game in his junior year, Steph declared himself eligible for the 2009 draft. He still had legions of doubters, though. At six foot three, Steph was above-average height for an NBA point guard. But he lacked muscle and it wasn’t clear he could handle the physical toll of NBA games or defend athletic guards in the pros.

“I heard the same stuff [I’d always heard throughout my life],” he says. “I’m too small, not athletic enough, can’t play defense, not strong enough.”

On the outside, Steph acted confident he could handle the next level. But inside, Steph shared some of the same concerns others had about whether he could make it in the pros. Steph was still baby faced, frail, and thin. How was he going to defend tall, muscular, or super-quick guards like Dwyane Wade, Kobe Bryant, and Tony Parker?

“I was nervous,” he told ESPN. “Obviously that transition is a big deal.”

Steph already was becoming a fan favorite, thanks to his sweet shot and boyish looks. When he was picked seventh in the first round by the Golden State Warriors, fans in Madison Square Garden erupted. Some cheered; others were upset he didn’t drop another spot so the hometown New York Knicks could grab him with the eighth pick. That year, Steph had a strong debut season, finishing with an average of 17.5 points, 4.5 rebounds, 5.9 assists, and 1.9 steals per game. He was unanimously selected as a member of the All-Rookie First Team and finished second in the NBA Rookie of the Year Award voting.

But his body began to become a liability, just as the experts had feared. In the 2011–2012 season, Steph missed forty-eight games, dealing with two ankle surgeries. Some wondered if his injury woes would become chronic and whether Steph would become another Grant Hill—a former NBA player with unlimited potential who saw his career cut short by ankle troubles.

“Every question I got was ‘How are your ankles?’” Steph says.

Steph spent six months rehabilitating, turning to his family for comfort and support. He tried his best to tune out skeptics who doubted his long-term prospects.

“It was really tough,” Dell recalls.

Many players get to the pros and are happy just to be in the NBA. But Steph’s goal was to be a star, not just an ordinary player. Steph had averaged eighteen points a game and 5.9 assists during his first two years at Golden State—impressive numbers, but not good enough to make an All-Star Team. He was determined to prove the skeptics wrong and show he could become one of the NBA’s best guards.

Steph already was a deadeyed shooter. His dribbling and ball-handling skills weren’t nearly as impressive, though. In college, the flaws in his game hadn’t mattered very much because he’d been a shooting guard until his junior year, which meant he’d often come off screens for open shots. He hadn’t needed to pass or dribble very much while filling that role. His teammates’ screens helped him get open looks at the basket. But now, as an NBA point guard, Steph didn’t have a chance at becoming an elite player unless he somehow turned his dribbling and passing weaknesses into strengths.

During the NBA lockout in the summer of 2011, Steph decided to rework his game, just as he had with his father as a child. It took a lot of courage for Steph to admit he was good but not good enough.

Steph hired a trainer and began intensive daily workouts at a local gym near his hometown of Charlotte, North Carolina, working on a series of unique and challenging drills, each with the goal of improving a different facet of Steph’s game. One drill, aimed at making Steph dribble with more force and confidence, involved dribbling two balls at the same time, one a normal basketball, the other a much heavier and less bouncy ball. By dribbling harder, Steph learned to move the ball more quickly from the floor to his hand, helping him navigate tight spaces on the court, moving in and out of traffic. The drill also made his hands faster and stronger.

Another drill involved tossing a tennis ball in the air, dribbling a basketball behind his back, and catching the tennis ball before it hit the floor. Steph’s dribbling and passing skills were getting better, but he wasn’t there yet.

His drills became more complicated and challenging. Steph performed a series of between-the-leg and behind-the-back dribbles with one hand while his other hand was occupied. Sometimes, Steph dribbled with one hand and waved a forty-pound rope in the other, for example. Later, Steph incorporated a drill in which he dribbled while wearing goggles that cut off vision in one eye, to improve his court vision and passing.

Over time, Steph’s dribbling became as extraordinary as his shooting. Now that he could dribble through traffic and around defenders with ease, he knew he’d have more space for his outside shot because defenders would have to respect his dribbling ability. He also was sure his passing skills had improved dramatically. Steph couldn’t wait for the season to begin so he could unveil his new all-around game.

In November 2012, Steph returned for his fourth NBA season. He was healthy, finally, still deadly from downtown and ready to unleash his revamped game featuring moves few had ever seen. Ankle-breaking crossovers. Quick changes of direction in super-tight spaces. Behind-the-back bounce moves. Steph's new skill set left defenders reeling. Just as he suspected, the moves created space for Steph to find open shots or to hit teammates with bull’s-eye passes. In the 2012–2013 season, Steph averaged 22.9 points, 6.9 assists, and 4.0 rebounds per game; he even scored a career-high fifty-four points in a loss against the New York Knicks, going eighteen for twenty-eight from the field.

As his game improved, Steph felt he deserved to represent the Warriors in that year’s NBA All-Star Game. Before a midseason matchup in Chicago, Steph waited in his hotel room for the Western Conference All-Star Team selections to be announced, sure his name would be called. The wait seemed to drag on forever. Finally, the roster was announced—to Steph’s shock, he didn’t make the cut.

Steph had been overlooked once again.

He sat in the room for several minutes, dejected. It was a disappointing moment he would remember for years.

Whenever he got down or experienced a rough game, Steph often returned to the Warriors’ locker room to find a text message waiting for him from his old college coach. Usually it was some helpful advice, sometimes in language that only Steph could understand.

Sleep in the streets, Coach McKillop often would text, for example.

Steph knew what the cryptic message meant— his old coach was sharing a lesson from former NBA player and coach Kevin Loughery. When life’s rough and you’re missing your shots or dealing with other kinds of disappointments, the only way to respond is to practice your heart out, even if it takes all night, leaving you locked out of your home and forced to sleep in the streets.

Coach McKillop was telling Steph that the best response to a setback is to work even harder.

Steph got the message.

Gonna be sleeping in the streets tonight, Steph texted right back to Coach McKillop.

Instead of dwelling on the All-Star diss, Steph decided to continue working on his game. Later that season, Steph set the single-season record for three-pointers and led the Warriors to the playoffs, losing in the second round to the San Antonio Spurs.

During the 2013–2014 season, Steph was rewarded for his hard work. This time, when the All-Star Team rosters were announced, Steph’s name was called. Not only did he make the team, but he was voted in as a starter.

The kid who many had thought had little to no chance of making the NBA was officially a star, finishing the year with 24 points and 8.5 assists a game.

At the end of the 2014–2015 season, Steph was named the NBA’s Most Valuable Player, adding to his resume as an elite player. To cap off his incredible season, Steph led the Warriors to victory in the NBA finals, defeating LeBron James and the Cleveland Cavaliers. Steph also had become one of the league’s most popular players, with the second-highest-selling jersey—at that, at least, he could not defeat LeBron James, whose jersey held the top spot.

Steph was on his way to setting NBA records. By the end of the 2015 calendar year, no active or retired player who’d attempted more than two thousand three-pointers could match Steph’s 44 percent shooting percentage. He also ranked fifth in free-throw percentage among qualified players, shooting 90 percent from the line.

“Curry three-pointers are like everyone else’s dunks,” the Wall Street Journal wrote that year. “Only his misses are surprising. To watch Stephen Curry play basketball is to witness a shooter unlike any the NBA has ever seen.”

In the winter of 2015, Steph visited Madison Square Garden, the mecca of the basketball world, for a showdown with the New York Knicks. He racked up twenty-two points with relative ease, hitting open men and putting on a dribbling clinic, flashing big smiles after nice plays and receiving the Garden’s loudest cheers, a rarity for a visiting player.

In the locker room after the game, while icing his knees and dealing with scratches on both arms—souvenirs from aggressive defenders who had failed to slow him down—Steph took time to share his thoughts on his unlikely career. That night, he had heard wild cheering at the Garden, Steph acknowledged. But he said he couldn’t forget the sting of the many insults and disappointments suffered years earlier, when he couldn’t manage to grab the attention of college recruiters, heard skepticism about his pro prospects, and then couldn’t crack the NBA All-Star Team.

“Two years ago, I was snubbed, and now I get accolades,” he said. “It’s crazy.”

Asked what advice he had for young people having their own troubles gaining appreciation and attention, Steph urged patience.

“Find your niche and find ways to have fun on the court, hold yourself to a high standard,” he said.

“If you have the right attitude, you’ll eventually get noticed. . . . Nowadays, scouts will find you, wherever you are.”

He shared other advice relevant for basketball and for life. Talent only takes you part of the way, he said. To be a success, much more is needed.

“If you dream big and work hard, you’ll see results,” Steph said with a smile. “It’s the hard work that separates you.”

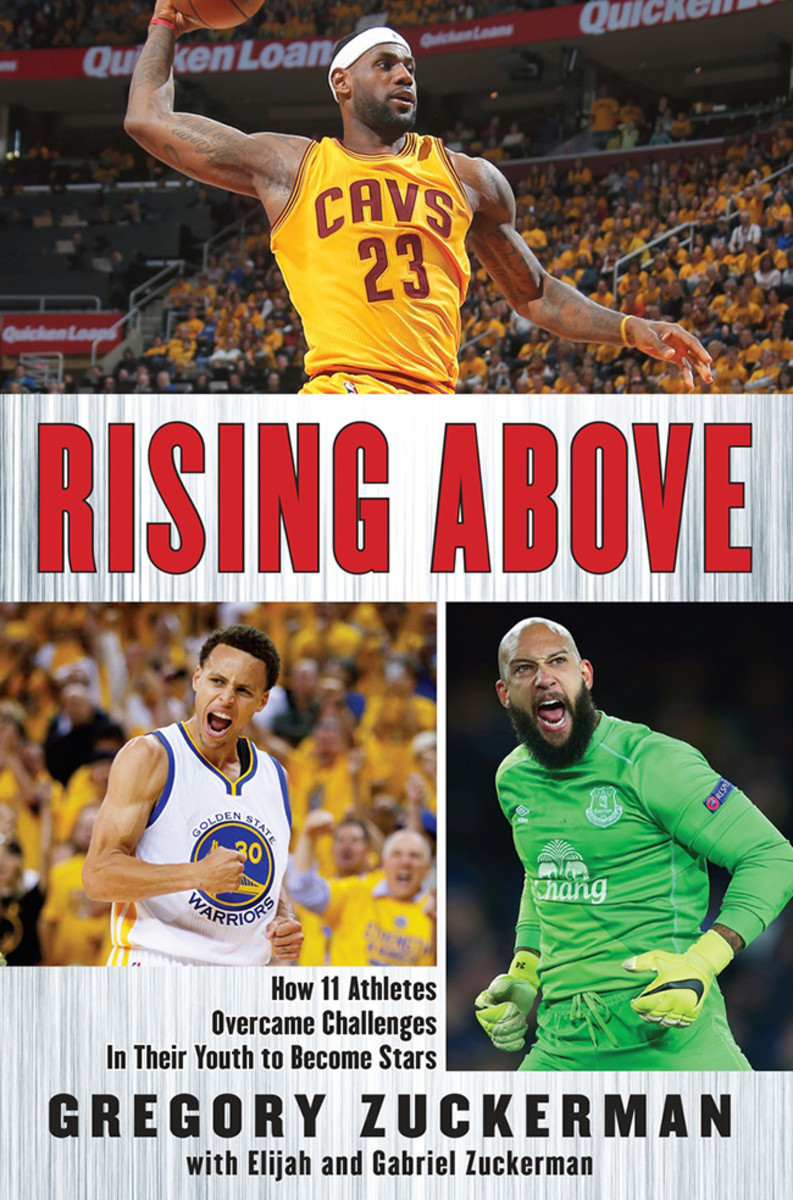

Rising Above is available in bookstores now. For more about the book, check out an interview with the authors!

Photos: Ezra Shaw/Getty Images (arms in the air), John Biever (Davidson action), Streeter Lecka/Getty Images (Davidson shot), Jesse D. Garrabrant/NBAE via Getty Images (Warriors), John W. McDonough (championship), Eric Risberg/AP (wax figure), Philomel/Penguin Young Readers (cover)