Inside the Totally Mad World of Spy vs. Spy

When you talk about MAD Magazine, two things pop immediately to mind. The first is Alfred E. Neuman, the wide-faced, gap-tooth cartoon mascot of the magazine. The second are the black and white spies locked in perpetual battle in the comic strip “Spy vs. Spy.” The triangular secret agents were created by Cuban artist Antonio Prohías in 1961 and introduced in MAD #60. Since then, the characters have been trying to outwit — and outgun — one another with increasingly outlandish scheme and plots that inevitably end in the (temporary) demise of one or both spies. And they’ve remained incredibly popular: the strip has been running non-stop for more than 50 years, and the spies have jumped off the page and into cartoon shows and video games.

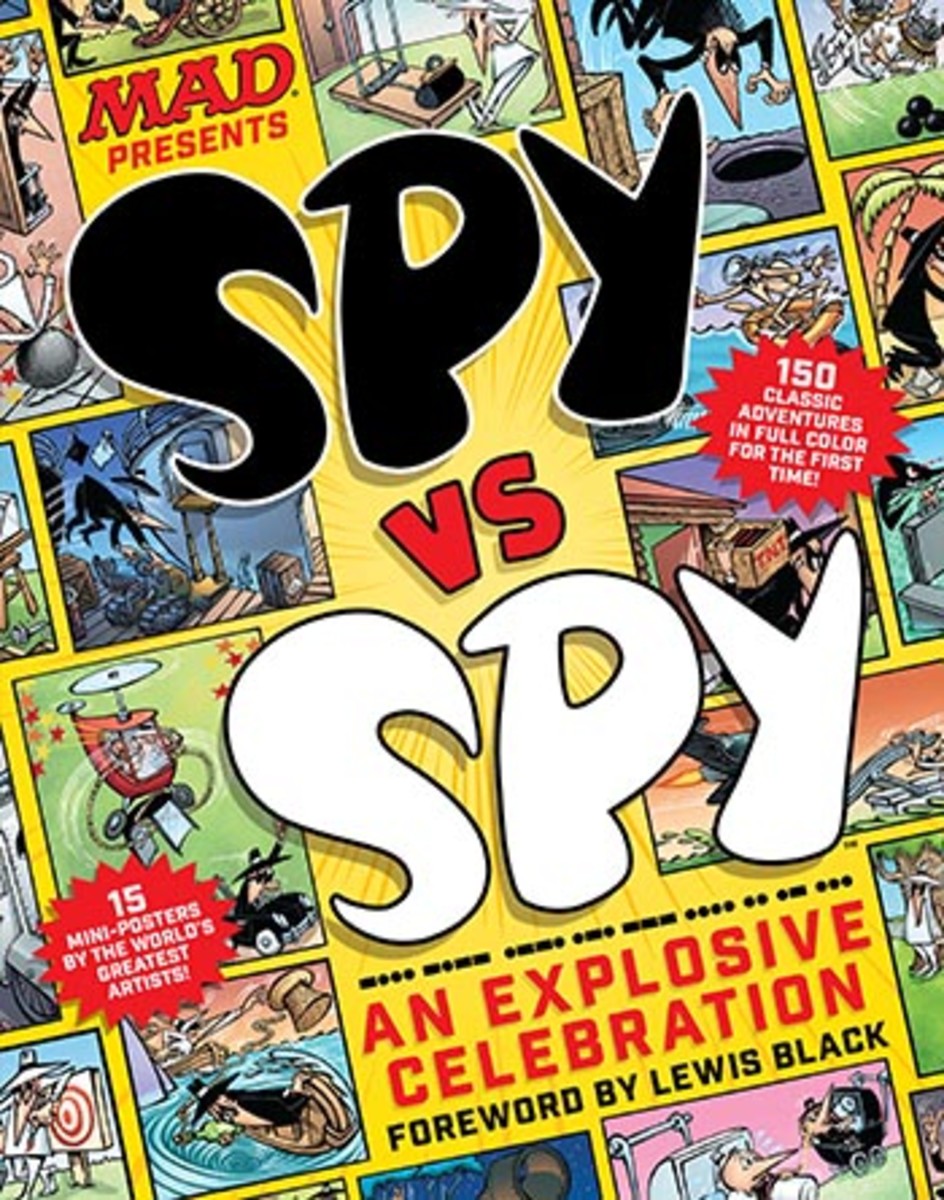

To celebrate “Spy vs. Spy,” the editors of MAD have collected 150 of Prohías’ original comics (which have been colorized for the first time — they were originally published in black and white) and paired them with the best of current “Spy” writer/artist Peter Kuper, in the book MAD Presents Spy vs Spy: An Explosive Celebration. The book also includes takes on the spies from superstar artists like Darwyn Cooke, Jim Lee, and Bill Sienkiewicz, among many, many others.

At New York Comic Con last month, SI Kids stopped by the MAD booth to chat with Kuper and John Ficarra, the editor of MAD Magazine, about “Spy vs. Spy,” how they keep coming up with crazy situations for the spies, and why it’s more popular today than ever before.

I used to read MAD as a kid, and in my mind it was always color. But then reading your introduction to the book I learned that it was published in black and white until really recently.

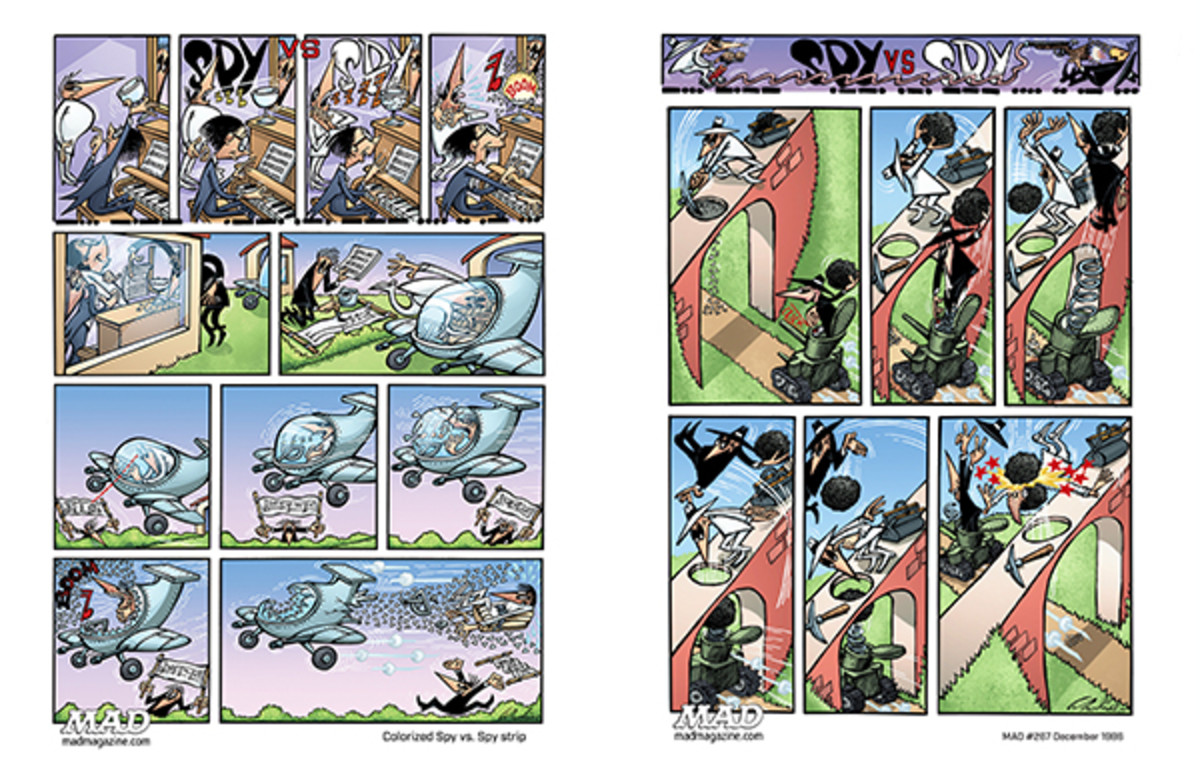

John Ficarra: No, we get that all the time. People just didn't think about it. But, what happened was, as the world became more colorful and video games and everything just exploded, the joke around the office was that MAD looked like it was printed in Mexico in 1959. We've got to up our game here a little bit. So that was actually the genesis of the book. When we started coloring stuff, we said, “Well, we shouldn't color ‘Spy’.” It's black-and-white. That's the whole gestalt of the strip. But what we said let's do one and see what it looks like. And we realized it just elevated it to a whole different level.

What's the process like of determining what went into the book? It's a lot of what was published originally, but not everything, right?

Ficarra: Well, we picked 150 of what we thought were good representations of Antonio Prohías' work. And then when we did Peter's section, we wanted to tell the story of Peter's transition from black and white stencil all the way up to what it is now, to colored stencil to the line and color art that he's doing now. So, while a lot of the book is Prohías, it's really a celebration of the entire “Spy” strip. So that's why Peter got a big section in there, and also we gave, I guess, 19 or 20 different artists' take on what they would do with “Spy.”

Peter Kuper: It demonstrates, like, how malleable the characters are and how many different directions they can go and still remain iconic.

In that period of time before Peter came on, were you running older ones or...?

Ficarra: No no no. We always ran new ones. [Duck] Edwing was writing most of them and he was a big gag guy. So I think the Spys are a little more slapstick than they are under Peter. I guess Bob Clarke did most of them, and Bob was very slavish to Prohías to the point where it didn't... it sort of zapped some of the life out of it. Edwing would send in these hilarious little doodles, but that's all they were, were doodles. We knew that we had to do something different, we couldn't continue on this path.

Kuper: I actually find it really difficult to work with another writer's idea, only in terms of I had to reconstruct it. There weren't too many of those. But it got to a point where I was, like, you know, I'm actually... The process of doing them, I'm writing, drawing, it's completely interlocked, the visuals of it, and so I had to reconfigure it so much that I realized... I mean, I can write them and so I really should. And then it was a much smoother process for me after that. Although, there was some really great writing in there and some great ideas coming down.

Click the image to see a larger version!

When the strip began, I think people had an idea of what spying meant and your imagination as a reader can sort of run wild. But now people are much savvier about what that world is and what the tools are. Does that make it harder to come up with concepts for the strip that will still capture people?

Kuper: No, unfortunately it goes the other way, which is that with drone attacks and things that you can do with cell phones, the NSA, it's kind of, like, bottomless. I wish there were fewer things to work with.

Ficarra: My favorites from Prohías and Peter are the low-tech ones. Those are always the best ones. You don't know what he's building, and he's got a bow-and-arrow with a suction cup on the end but it's shooting across and it's taking this... That's when I think “Spy” is at it's best.

Kuper: The parameters of the strip are so wide that, for me, I just look at Prohías' work before I start doing a strip as a sort of warm up, and it's always, like, Oh, right, he did that. Oh, they're younger. You can explode somebody's head by blowing it up like a balloon. He really left a wide-open playing field, and so it's so... I'm sometimes surprised, like, wow, he really made this possible to go on for the foreseeable future.

Do you ever get to a point where you think...

Kuper: What's next? Oh, absolutely. I mean, I've had days where I'm staring at the ceiling… It’s very hard to explain to my wife what I'm doing sometimes. It's like, “Yeah, I'm working, yeah, can't you tell?”

Ficarra: And she says the rent is due. And suddenly he gets an idea!

Kuper: Yeah, exactly. It's like, hold on, wait, so he's playing with some money and… Sometimes I actually just start doodling and I'll just draw their faces and, oh, there's a... wait, it looks like one of those traffic cones, or an ice cream cone or something. So sometimes I'm just staring at actual physical things and then doodling really helps with that. I also keep a perpetual back-pocket sketchbook, and so every time, I'll just be on the subway and I'll just draw something. So I have these little bits and pieces I can run to. And so in the time between issues, I'm just sort of steadily… it's perpetually buzzing in my ear, and so I have that going. But sometimes the day will go by and I do a lot of sketches and I realize there's nothing there and I feel like it was a wasted day and the next morning I wake up and I have three ideas.

Ficarra: Yeah, Peter's upped the bar, too. Prohías sometimes would do a little freeze with the logo and then the strip, but Peter does a somewhat intricate freeze with the logo, then he does the strip, and then he does a little side four- or five-panel strip, too. So he's made life harder for himself, but it's better for the magazine and the reader.

Flipping through your portfolio you've illustrated covers for Fortune and Time. You've mentioned drones already, but how much other sort-of real-world politics do you draw from for the strip?

Kuper: It's bits and pieces. They live in somewhat of a separate universe that way. It's more eternal that Obama or Trump. But there's occasionally... I did one, I think, when I was living in Mexico where one of them is a piñata, which works perfectly with the pointy nose, but then trying to get across the border. And so I can throw some things like that into it periodically... I did something on global warming. And I could probably do a lot more climate change things in some variation. But they sort of live in a parallel world that has got all these various dangers but doesn't necessarily like land right on it. I like the more eternal aspect of it.

Click the image to see a larger version!

This time we're in right now, with presidential primaries, is this, like, high season for MAD?

Ficarra: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I mean, we love doing political humor, and our blog every day is filled with political humor. We just did an issue with five different political posters in it. Ben Carson as Dr. Nolittle.

Kuper: Great for the posters, especially.

Ficarra: We continue to... whack away at them.

What's the future of the “Spy vs. Spy” strip? Where does it go from this thing that was black and white, and now it's in color...?

Ficarra: I think you're going to see a lot more spies in other media. And that's pretty much all I can say at this point. But there are...

Kuper: I'm working on a 3D printer version of it. It's going to be pop-up spies.

Ficarra: Believe it or not, they have that technology. I looked into that, taking the...

Kuper: I know. It's coming.

Ficarra: It's something that we've talked about in the office.

I know why I like "Spy vs. Spy" as an adult and why I liked it when I was younger. But what about it makes it something kids still love to read?

Kuper: I think war is just one of those eternals, it's like it's built into our DNA. And that conflict — it can be conflict between kids, it can be a playground thing — I just think that that's part of human nature, and this represents that in a really distilled way that people just naturally identify with.

Ficarra: Well, first of all, obviously no words. And it's all graphic and so much of everything now is just graphic, on your iPad or anything else. What's the phrase, they're native to that stuff? And Peter really plays well to that. So I think it's always a perennial favorite thing. I also think, because there's no words, this and Sergio Argones are two of [things] that we use to get kids into MAD.

Photos: Copyright © 2015 E. C. Publications Inc. Published by Liberty Street, an Imprint of Time Inc. Books. All rights reserved.