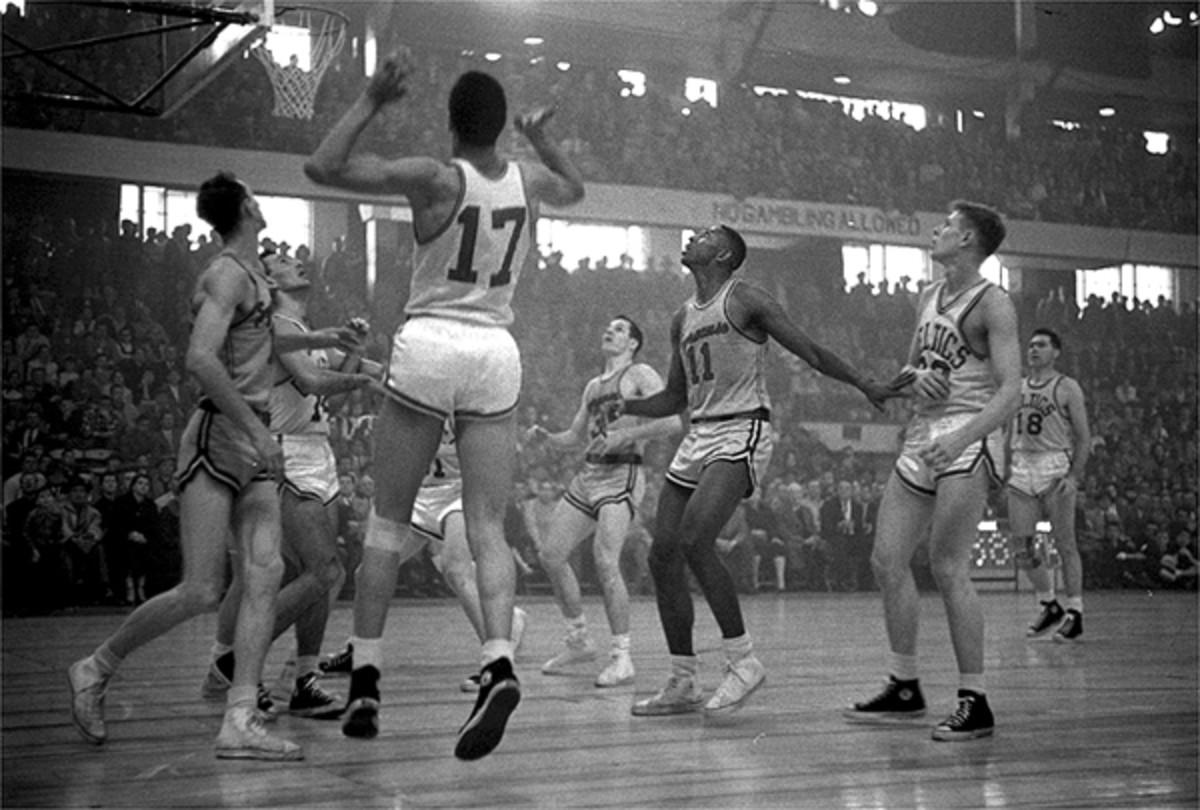

Basketball Legend Earl Lloyd and Other Sports Pioneers Left a Lasting Legacy

Last week, former basketball star Earl Lloyd died at the age of 86. Nicknamed the Big Cat, he scored 4,682 points over his nine-year pro career and is ranked 43rd all-time on the NBA scoring list.

But his importance to basketball — and sports — is bigger than what he did on the court.

Earl Lloyd was the first African-American to play in the NBA. He was one of thee African-Americans to enter the league during the 1950-51 season. But because he signed his contract and played his first game before the others, he’s credited for breaking the league’s color barrier.

In 1955, Lloyd and black teammate Jim Tucker helped the Syracuse Nationals win the 1955 NBA title and became the first African-Americans to win a championship. When his playing days were over, Lloyd became the league’s first African-American assistant coach (with the Detroit Pistons) and went on to become the fourth African-American head coach, and first who wasn’t a player coach, when the Pistons promoted him early in the 1971 season. He only coached that one year. In 2003, he was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Throughout his life, Lloyd credited Jackie Robinson as a role model. Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier in 1947, which helped pave the way for diversity in sports. “Jackie made things a lot easier for me,” Lloyd said in a 2010 radio interview.

But Lloyd had a big impact, too. He inspired many young black athletes through his modesty, hard work, and courage. And his story reminds us that while Robinson might be the most well known African-American sports pioneer, he’s not the only one.

So, in honor of Earl Lloyd and his legacy, we look back at the men who helped integrate the other three major American sports.

MLB: Jackie Robinson

After playing a season with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues, Robinson broke baseball’s color line when he took the field with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. It wasn’t an easy transition. He was treated poorly by fans, other players, and even some teammates. But Robinson was reluctant to let his frustration show. “I had to fight hard against loneliness, abuse, and the knowledge that any mistake I made would be magnified because I was the only black man out there,” he wrote in his autobiography, I Never Had It Made. “Many people resented my impatience and honesty, but I never cared about acceptance as much as I cared about respect.” He persevered and was named the National League Rookie of The Year in 1947 and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962. Following his death, his widow, Rachel, founded the Jackie Robinson Foundation, an organization to help African-American children receive a better education. And today, his number 42 is retired across Major League Baseball in recognition of his importance to America and its national pastime.

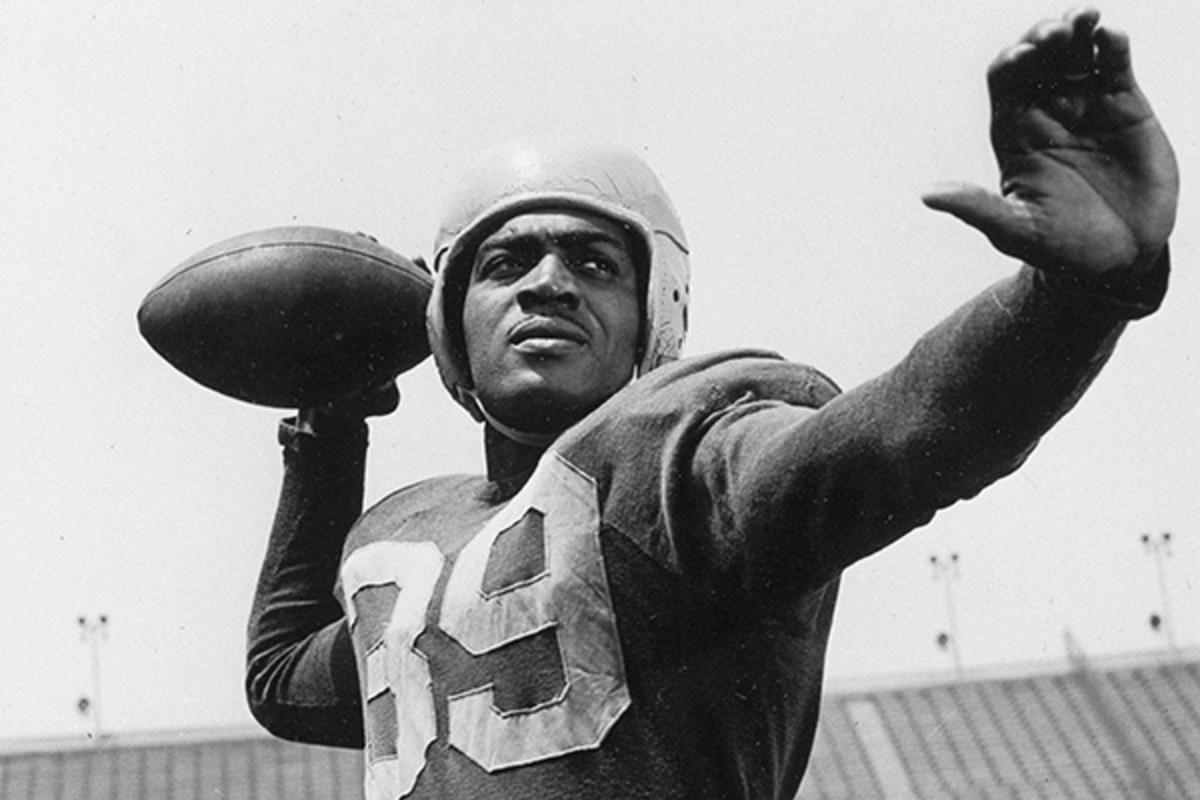

NFL: Kenny Washington

Washington went to college at UCLA, where he played football with Jackie Robinson and led the nation in offense as a senior, in 1939. The Cleveland Rams signed Washington on March 21, 1946, after he had worked in the Los Angeles Police Department and played four years of minor league football. Knee injuries kept his NFL career short. He only played for the Rams for three seasons. But by taking the field, he opened the door for countless other African-American athletes to play professional football. (A documentary about Washington and the other members of the Forgotten Four who integrated the NFL was released last year. You can find out more about Washington and the Forgotten Four in Kid Reporter Max Ferregur’s story about the film.)

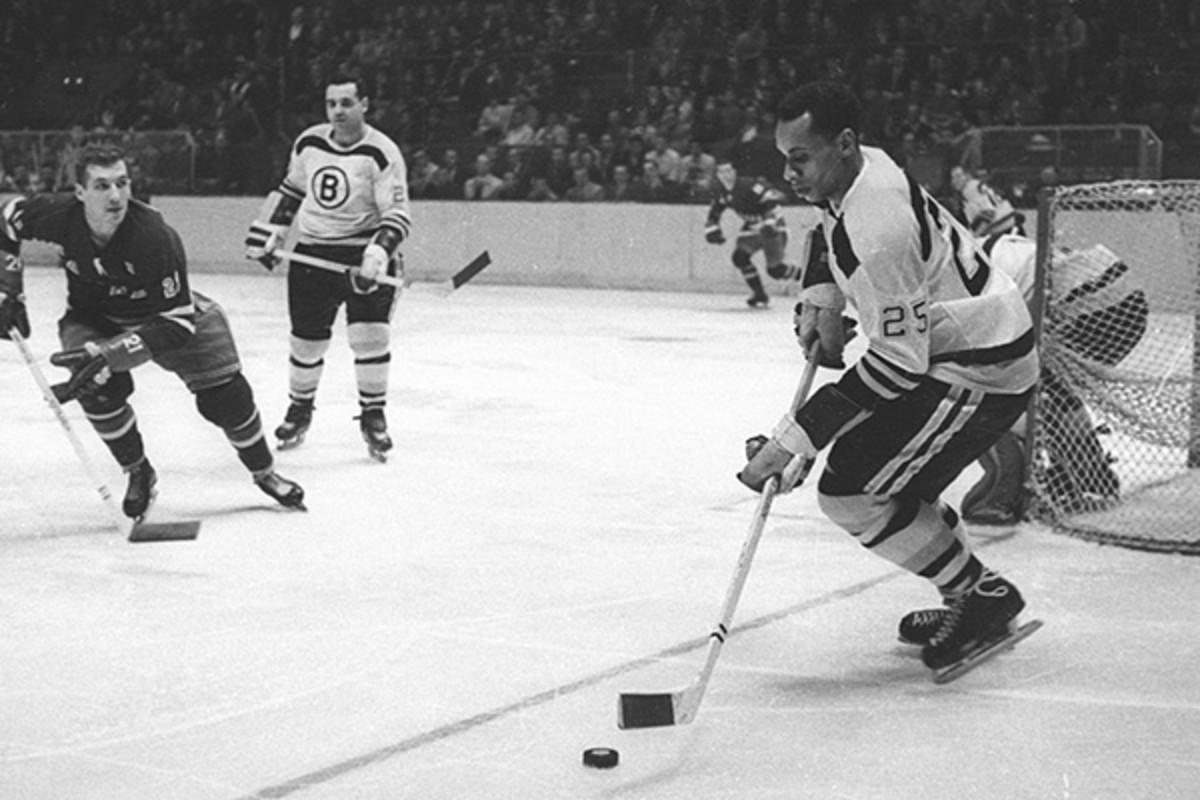

NHL: Willie O’Ree

O’Ree, who is from from Fredericton, New Brunswick, in Canada, integrated the NHL a full decade after Robinson played his first game. O’Ree played two games for the Boston Bruins in 1957, and though he only played one full NHL season (1960–61), he enjoyed a long career playing in other leagues until 1979. And he did it despite being legally blind in his right eye. Like Robinson, O’Ree had to deal with racism from fans. He encountered it in both the U.S. and Canada, but Americans were far worse. “Fans would yell, ‘Go back to the South’ and ‘How come you're not picking cotton?’ Things like that,” O’Ree told NHL.com in 2007. “It didn't bother me. I just wanted to be a hockey player, and if they couldn't accept that fact, that was their problem, not mine.” He was inducted into the New Brunswick Hall of Fame in 1984 and was awarded the Lester Patrick Award for outstanding service to hockey in the United States in 2003. After his hockey career, he played a large role in helping the NHL achieve more diversity.

Photos: Evan Peskin/Sports Illustrated (Lloyd), AP Photo, File (Robinson, Washington), Getty Images (O’Ree)