NBA Star Grant Hill's High School Retires Jersey

In December, College Basketball Hall of Famer and former NBA star Grant Hill had his jersey retired by his alma mater, South Lakes High School, in Reston, Virginia. Hill, who played college ball at Duke and is the son of former NFL running back Calvin Hill, sat courtside as the South Lakes Seahawks boys varsity basketball team beat West Springfield 77–60. During his time at South Lakes, Hill won two district championships (1986, ’88) and a regional championship (’89) en route to establishing his legacy and becoming arguably the best basketball player to come out of the area. (He went on to play in the NBA for the Pistons, Magic, Suns, and Clippers.) After the game, I had a chance to speak with Hill about life, school, and, of course, basketball.

It has been 27 years since you last played a game for South Lakes. What does it mean to you to have your jersey number retired by the school?

It’s great. It’s awesome because South Lakes was where the dream all started with [former head basketball coach Wendell Byrd], the staff, my teammates, the opportunity to play here and grow and establish myself as a player. That foundation stayed with me in my career and the rest of my life.

Watching South Lakes basketball play today, are there any differences between this team and the team you played for? How would they stack up against your team?

We were pretty good back in the day, because we had height. I played point guard [Hill is 6’8”], and our shooting guard was 6’6”, so I’d like to think we would do pretty well. But [the current varsity] looked pretty good.

How has then on-court interactions between players on opposing teams changed from when you played?

I don’t think that in high school there was very much trash talk. First of all, we were pretty good, but we didn’t win every game. We would travel to state finals and tournaments, but trash talking wasn’t something that was real big. It happened here and there, but we were pretty dominant, and Coach Byrd kept us focused on the goal at hand, which was to try to keep our emotions in check and try to win the game.

You grew up with a dad who was a former NFL player and was very well known. To what extent did that affect your high school life?

My father [being an athlete] helped because I was around sports my whole life, and whatever I was experiencing he had done. To have him as a resource and someone to give me perspective was huge for my ability to grow and learn from mistakes, to understand through sacrifice and hard work. In high school and college, and even my pro career, to have a father who was a professional athlete himself was hugely beneficial.

If you could change one thing about your time at South Lakes, what would you change?

I would probably focus on basketball as a sport primarily and do some other clubs and organizations.

What is your greatest memory from being at South Lakes?

When I was a sophomore, were playing in our district championship game here at South Lakes, and it was packed, standing-room only. We were playing Washington & Lee, and they had Crawford Palmer, who was a McDonald's All-American and went to Duke; I actually played with him for a year. I scored the last 16 points of the game and hit the game-winning shot on an alley-oop slam dunk, and that was kinda like my coming-out party and really helped propel me and gave me confidence.

If you could give the ninth-grade you one piece of advice, what would it be, knowing everything that you know now?

I think we all would go back and give ourselves advice, but one of the things is that you learn from failure. I failed a lot and made mistakes, but it’s all a part of growing. I would encourage myself to not fear failure. As my mom used to say, “Don’t fear failure; fear success, because people in life are ruined by success,” and so fear is just an illusion. I think [I should have been] more confident. I was very shy, and I’ve grown since then.

Your mom wanted you to go to Georgetown, and your dad wanted you at North Carolina, but you chose Duke. What was that time in your senior year like?

I made my decision at the beginning of my senior year, right when school started. I think my parents were supportive of me regardless; I think they had their favorites in schools and where they wanted me to go, but they really encouraged me to make my own decision. They quickly grew to love Duke; my mom is on the board of trustees at Duke, and she’s embarrassingly more engaged there than I am.

You played four years at Duke, which was uncommon then and even more uncommon today. As a former NBA star and current owner, do you think that players could benefit from going to college and potentially playing all four years?

There are players who are ready to come right into the NBA and thrive on and off the court, and we have loads of examples of players who have done that. I think we have to take a hard look at the model: Is it working, or is it flawed, and what can we do for the game, for players? There’s not an easy fix or a simple solution. I do think in the process we’ve sort of devalued the importance of education and how that plays a role in one’s career. I do have a little bit of a problem with that, but it’s not an easy solution. I know that [NBA commissioner] Adam Silver and Michele Roberts, the head of the Player’s Association, are looking at it, and I think that collectively we are trying to figure out what is the best decision for everyone involved.

Could maturity play a part in that as well?

From an NBA standpoint there’s more of an emphasis on player development. [For instance], when I came out of college, you had a head coach and two assistants, and that was pretty much your staff. Now, on the Atlanta Hawks, we have a head coach, three assistants, and, maybe 12 other coaches who are there to help players become better. We have the resources to help players transition into the NBA and deal with all the potential pitfalls of being a professional athlete, and that wasn’t around 20 years ago. Because kids are younger there is a real need for that, so it’s really case by case. There are guys who have gone to school for four years who are very juvenile and flamed out as professionals, and there are examples of guys who were very young but had great, productive careers and were great ambassadors for the game, so it’s hard to make a blanket statement about ages of players.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

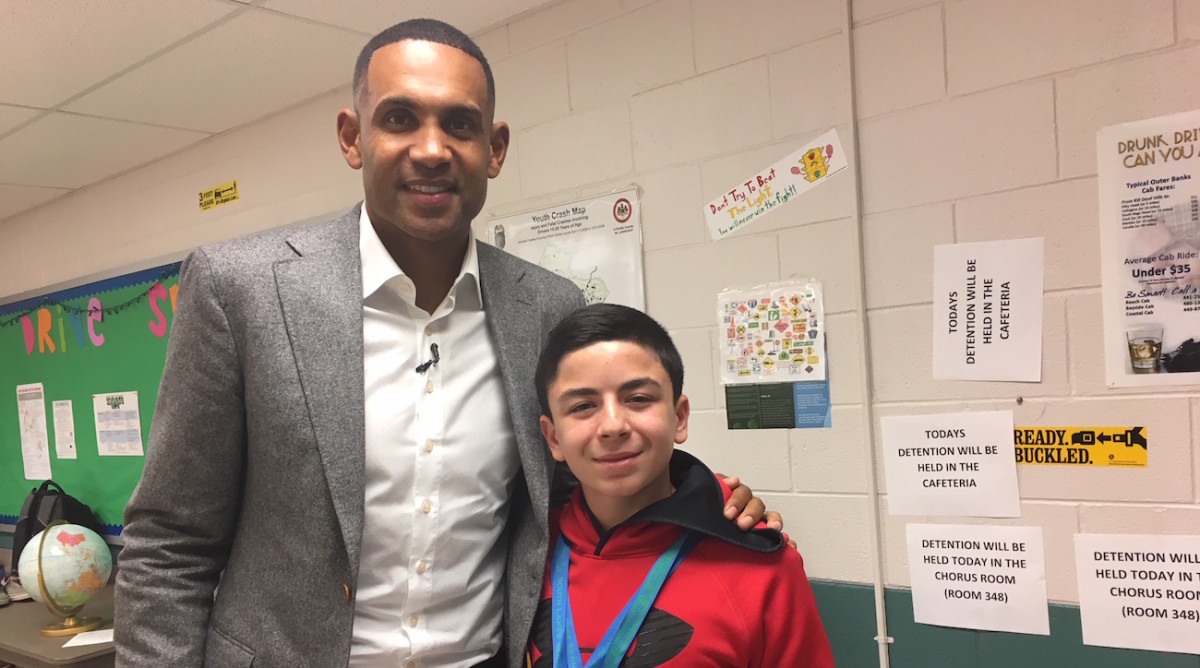

Photographs by (from top) Pete Marovich For The Washington Post/Getty Images (2); Doug Pensinger/ALLSPORT; Noah Shubert