R.A. Dickey, Tim Wakefield, Charlie Hough and the Art of the Knuckleball

Back in 2005, R.A. Dickey's pitching career was drifting along unremarkably. The righthander, who had been drafted by the Texas Rangers nine years earlier, had bounced around the minors, making occasional stops at the big league level and throwing a 93-mile-per-hour fastball but producing nothing special. "We thought this guy may be out of baseball pretty quick if we didn't suggest something," says former major league great and ESPN Sunday Night Baseball analyst OrelHershiser, Dickey's pitching coach at the time.

So Hershiser and then Rangers manager Buck Showalter had an unusual idea to help Dickey save his career. On off days and occasionally in games Dickey experimented with an odd and unpredictable pitch — the knuckleball. They told him that the best way to avoid a potentially permanent demotion to the minors was to become a full-time knuckleballer.

[R.A. Dickey Wins His 20th Game]

Now in his sixth full season as a knuckleballer, Dickey has become one of the most dominant pitchers in baseball. At age 37, the New York Mets ace threw back-to-back one-hitters and made his first All-Star team this season.

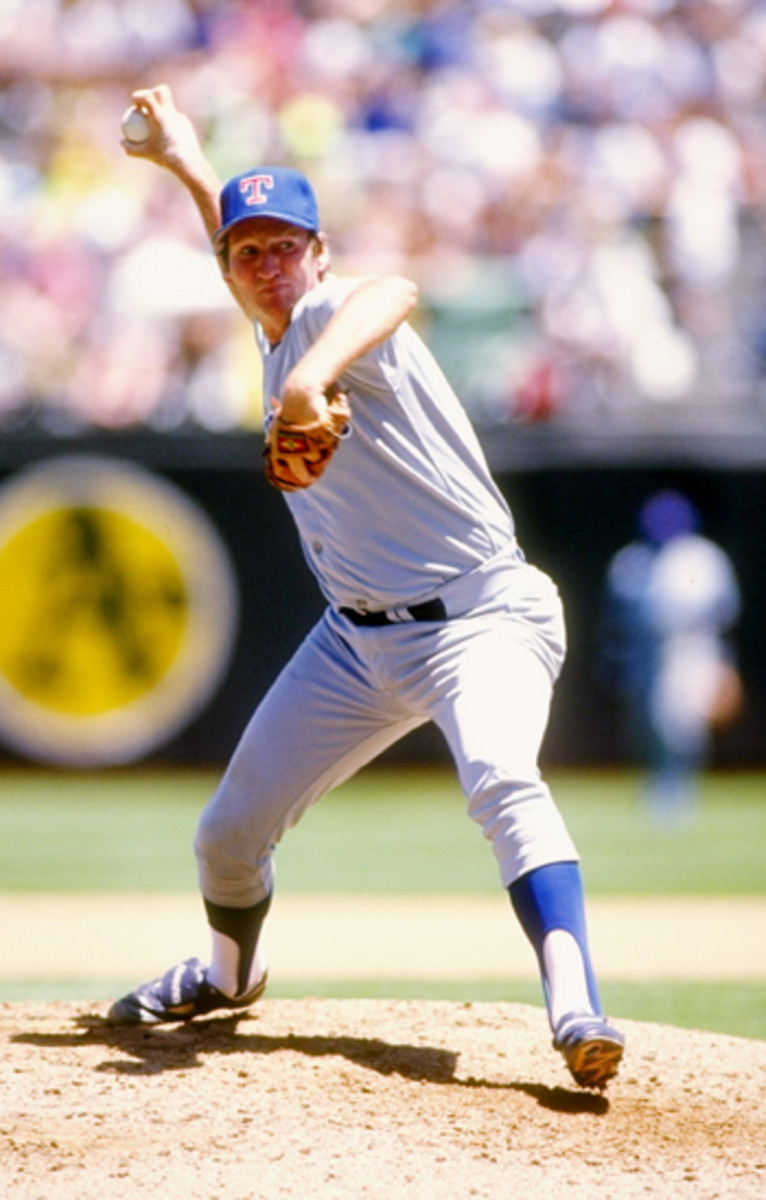

The knuckleball can be a magical pitch, one that doesn't require superhuman strength yet still makes some of the best hitters in the game swing, whiff, and shake their head at how badly it fooled them. Considering it revived Dickey's career, you'd think that more pitchers would want to throw it, but in MLB history only a handful of players have mastered it. Because the pitch is unpredictable and difficult to learn, not many can teach it and even fewer teams are willing to give a knuckleballer a chance. "When done well, it looks very easy," says Charlie Hough, a big league knuckleballer for 25 years, "but it's awfully hard to do."

Rare Form

Watch a knuckleballer and you'll notice that he has very different mechanics than conventional pitchers. Knuckleballers look more like they're throwing a dart rather than hurling a ball as hard as they can. They pitch that way to prevent the ball from rotating as it travels to the plate. The lack of rotation causes it to move unpredictably. Batters describe the pitch as fluttering toward them, making it very hard to hit. In order to control the spin, however, knuckleballers throw at a much slower speed, creating a fine line between success and failure — if the ball spins, it's no longer a baffling pitch but an easy target.

It all begins with the grip. The name is a bit misleading because the pitcher doesn't hold the ball with his knuckles, instead he uses the tips of his fingers. To make sure he has a firm hold, he digs into the leather cover with his fingernails, making their maintenance essential to pitching well. While power pitchers worry about pulled muscles or torn tendons, knuckleballers fret about the state of their nails. Losing a "fingernail would have been like having Tommy John surgery," Hough says.

Once the nails are honed, knuckleballers must train to release the ball in an almost unnatural way. Conventional pitchers snap their wrist forward so that the ball rolls off the fingers, imparting spin. Knuckleballers bend their hand back and keep their wrist stiff. Instead of snapping forward to release the ball, they extend their pointer and middle fingers to push it out of their hand. "It's quite a trick to do it," Hough says. "Your two fingers are different lengths, and you're trying to push them out with the exact same pressure on each finger so the ball doesn't turn."

After mastering the release, they then have to work on their pitching motion — or lack thereof. In order to avoid putting spin on the ball, knuckleballers cannot twist and turn or let their arm move too far away from their body. The mental image knucklerballers use to keep their throwing motion compact is to pretend there's an open door in front of them. When they move toward the plate, their whole body and arm must fit through the opening, which they refer to as pitching through the doorframe.

A Knuckleball Brotherhood

Pitchers rarely begin their careers as knuckleballers. In 1989, Tim Wakefield, who retired from the Boston Red Sox after last season, was in the Pittsburgh Pirates' farm system as a struggling first baseman. His coach noticed him goof around with the pitch and saw potential in his arm that he didn't see in his bat. Wakefield says the team gave him a choice: " 'You're going to convert to a pitcher or we're going to release you and you're going home.' So I said, 'OK,' " he remembers.

Hough started out as a conventional pitcher. "I had a shoulder injury in 1969, and it was just not getting better." So his minor league manager, Tommy Lasorda, said he should give the knuckler a try because it would put less stress on the arm. But he had a problem: Who would teach him?

With so few knuckleballers, it's a challenge to figure out how to throw it effectively. "You try to seek out someone who has done it, and there are only a few guys," Hough says. "I got to meet Phil Niekro when I came to the big leagues, and I got to play with [Hall of Famer] Hoyt Wilhelm. I learned from the two best."

With his success, other aspiring knuckleballers have come to Hough to learn how to make it in the big leagues. When Wakefield debuted in the majors in 1992 with his knuckler, he was a sensation on a Pirates team that narrowly lost Game 7 of the National League Championship Series. He won all but one of his games that season. But when Wakefield began to struggle with the pitch, he sought the help of Niekro, Hough, and Tom Candiotti, who taught him how to change speeds, pick spots with hitters, and be patient when it didn't work. "They welcomed me into that fraternity with open arms," says Wakefield, who played on Boston's 2004 and '07 World Series championship teams. "It was a feeling of comfort that you could finally talk to somebody that went through what I was going through."

Then came the opportunity for Wakefield to pay it forward to Dickey. When the Rangers first converted Dickey, they sent him to Hough to help him learn the pitch. Dickey didn't stop there though; he approached Wakefield, who gave Dickey special access to watch him throw in the bullpen. "I don't think you'd want another pitcher helping a pitcher on the opposing team," Wakefield says, "but knuckleballers share a lot."

Eventually all the advice and determination paid off, resulting in a devastating knuckleball for Dickey, which he can throw harder than any of his predecessors. While Hough and Wakefield still have minor leaguers asking them for tips, Wakefield's retirement leaves Dickey to carry the torch for the pitch until another team gives a knuckleballer a shot. What will bode well for Dickey is that knuckleballers last until a ripe old age; Hough pitched until he was 46, and Wakefield until he was 45. "R.A. is late in his career at 37," Hough says. "But he's going to have plenty of good years." After all, he has proven that he has mastered the art of the knuckleball.